P O R T U G U E S E | K N O C K | D O W N

A cement wall of black water smashes into my back. I've never been hit by anything with such great force, it catapults me with wicked pressure through mid-air and I am hurled up and over the helm, missing the cockpit combing and winches on the leeward side, breaking straight through the lifelines and shredding the lee cloth at the seams. I open my eyes underwater. Fully submerged. I see bright green, bubbles are lit by my headlamp. My eyes sting with salt. I don’t feel the cold, not yet. It’s silent. In my foul weather kit, I am a weightless astronaut under the sea.

P O R T U G U E S E K N O C K D O W N || Cabo de Sao Vicente, Portugal. || A p r i l 2 0 1 8

F o r w a r d // I appreciate that since ships have sailed, they have been knocked down. There are countless capsizes recorded, and just as many unaccounted for versions of this story. The first time you get knocked down, you don't forget it. The lessons learnt are significant. I share mine with caution as many sailors have experienced far worse. For some, a single knock-down may be minute in comparison to the rest of their story.

Our version, is not to be over dramatized. It is not written to intimidate, to put off, nor to have the most epic bar story. It is a scenario every ocean sailor avoids at all costs yet often encounters. With that said, I have had a hard time putting down on paper, as the possibility of it being picked apart by other sailors has put me off. I've narrated my piece exactly as I remember it, alongside Lukes technical notes.

We are aware we did not do everything right and took away with us many should haves, could haves, and would haves.

L u k e : Passage from La Coruna, Spain, to Lagos, Portugal 450 nautical miles. April 6, 2018. Mazu downloaded forecast 15-37 knots W-NW for whole sailing area. Three days in, Tuesday afternoon progress good. Weather as predicted. Tuesday sunset watch, winds increasing. Large squalls in excess of 40 knots. Luke on deck dropping staysail when Jessie clocked first 49 knot squall at 20:00.

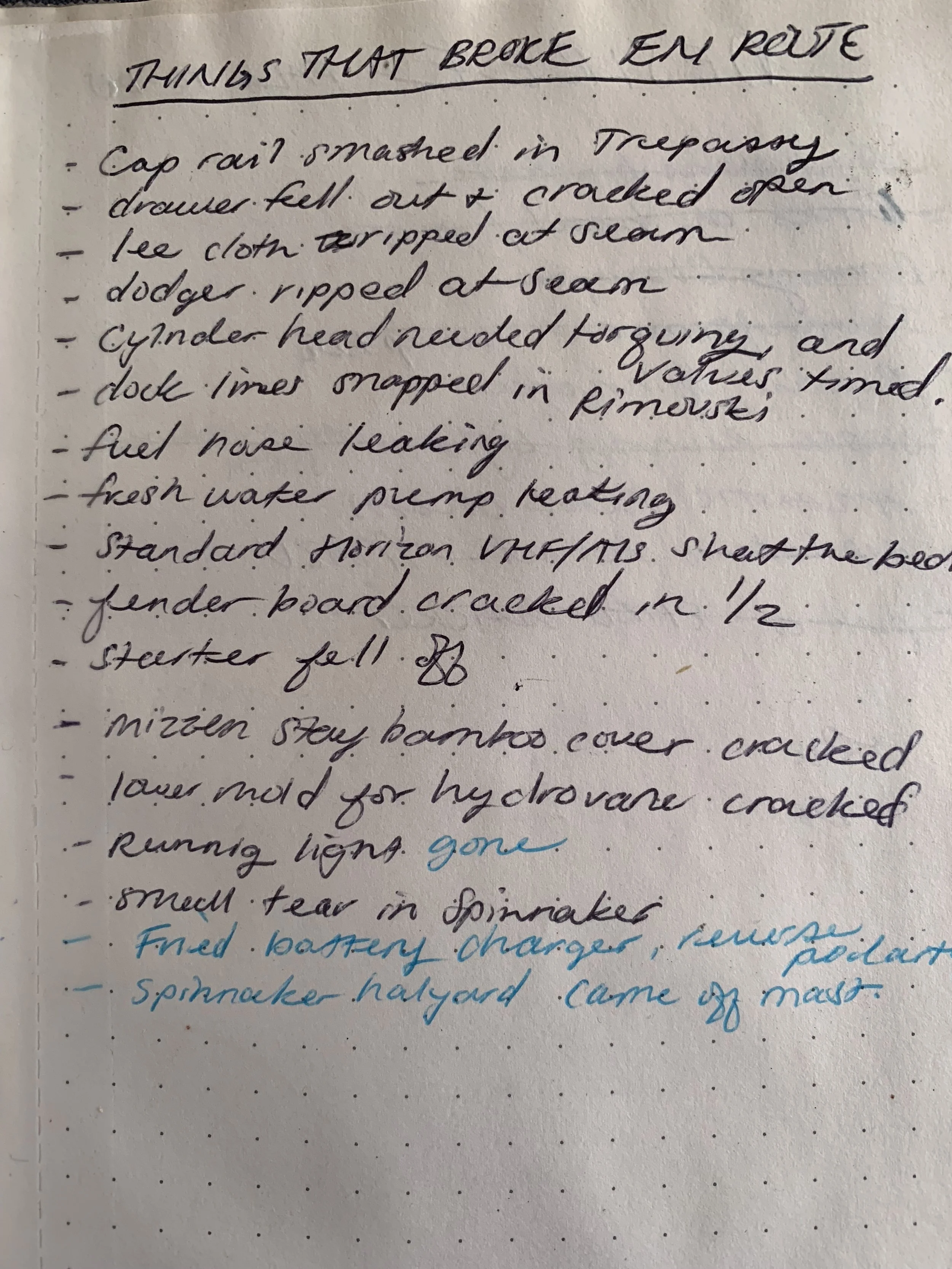

Winds easing thereafter. 30-40 knots with less squalls, which were less violent, roughly as predicted. Sailing with “Trepassy reef`” (smaller than a third reef, not tacked or clewed, resting on lazy jacks) Boat speed reduced from max surf of 13.7kts to approx 10 knots. Squalls continue until watch change at 01:00.

Luke on watch. Hydrovane begins to struggle with large quartering stern waves. Wave pattern consistent. Hand steering assist. One accidental gybe by Jessie, arrested by preventer, no broach, just re-gybe back onto starboard. Taking 20 minute shifts at the helm, air temp appx 12 degrees C. Both sailors on deck in light of rough sea state. Lifejackets on, tethered in cockpit. Boat requires constant helm in-put to hold course to waves, typical for this boat in rough seas. Boat on edge, but under control. Progress good. Both sailors good. Sea state remains consistent.

GPS logged position 37° 4.2 north, 9° 9.3 west, heading of 150, TWA (true wind angle) 150-160, at 01:21 a max speed of 16.4 knots recorded, dropping shortly after (26 seconds) to 2.6 knots. This is when the wave struck approx 90 degrees to course, at 240 degrees. 60 degrees further to the right than the existing and consistent wave pattern over the starboard beam.

We don't roll all the way over. We don't even do a 180. But the violence of it all has me very disoriented. It's only a matter of seconds, 15, 20 max, life defining seconds as one would call them.

Desirée rights herself and I’m hoisted back into the cockpit. I couldn't find my tether and used a spare line I bowlined to myself 30 minutes ago. This piece of string just saved my life and I recognize immediately I would be long gone if it weren't for it. I think I will mount it on my wall back home. It's black with red stripes, and might look nice in my kitchen. Heavy, and waterlogged, I'm trying to figure out how to get back into the cockpit. My upper half is folded onto the leeward deck, my lower half still in the sea and dragging. It's true you gain super powers when adrenaline kicks in. I hoist up my lower half and feel the tug-of-war from the sea.

The sky is a clouded pool of black ink. I don’t see Luke. I scream for him. My first terror is that he has gone overboard. The kind of terror you don’t wish upon your worst enemies. I panic. A sailor’s worst nightmare. He grips my arm. He’s here. He’s right here. He helps me to my feet. I look up to see the rig still intact. He asks if I’m injured. I say no. Even if I were I wouldn’t recognize it. I ask him if he’s injured. He says no. I don't know what to say or what to do so I grab his face and kiss him. Hard. I don’t yet comprehend the gravity of the situation. He grabs my shoulders and checks me back into reality. He asks me to go check the bilge. I wipe the salt from my eyes and get to work.

L u k e : The boat heeled beyond 100 degrees, likely up to 110 or 120 degrees, born witness by vertical movement of interior objects and removal of mast head instruments. Wave hit sailors directly from behind. No visibility or warning of its arrival. Both crew thrown to leeward and submerged completely. Jessie washed through guard rail with massive enough force to rip the leeward weather cloth from it’s attachments. Tether stayed connected. Luke (helming at the time of wave strike) thrown over top of the wheel and binnacle, landing on the leeward side cockpit combing completely submerged. Tether stayed connected. Boat knocked down for approx 15 seconds then self-righted dragging Jessie back into the boat. Somehow crew had switched positions fore and aft after recovery.

We work efficiently, prioritizing safety. The dodger has been ripped off at its seams, leaving the stainless steel frame intact and no more cockpit protection. The once secured solar panel flaps violently. I cut it off and chuck it below. The GPS is dislodged from its mount on the dodger frame, chords ripped out. We lie a-hull and let the sea take us while we inspect damage. I approach the companionway where we had only one hatch board in - big mistake. I take one step into the cabin and there is no place to plant my foot. The ladder’s been dislodged and is strewn across the leeward berth. I cautiously climb down in the wet cave. I'm amazed at where things have landed.

L u k e : Squalls eased with max winds 38 knots, but averaging 30 kts which felt very comfortable compared to earlier conditions. Large quartering waves causing steering issues. A quick check of the boat confirmed the rig intact, sails intact. Inspecting interior confirmed bilge full of water, several items floating, and much of interior thrown to leeward including many heavy objects like floorboards and 7 gallon jerry can of water. Leeward berth would have been a dangerous place for crew member during the knock down.

First actions were leaving the boat lying a-hull and placing the Edson bilge pump downstairs (1 gallon per stroke) Biggest concern was another knock down, leaving enough water to flood batteries and engine. Water was cleared within 20-30 minutes with confirmation no further ingress. Made PanPan call on channel 16, No response.

Every thing on the starboard side relocated to the port. Shit. Is. Everywhere. The OCD side of me is in hysteria at the sight of everything out of place and drenched. The heavily weighted floorboard flew to the port side top bunk. Unopened cans of AWLgrip and West Systems chucked out of secured cabinets and across the saloon. The 7 gallon jerry can of water relocated to the top of the stove. The full bilge spills over onto the floor. I pick my Canon 5D out of the highest part of the bilge and say a little prayer. The suctioned ice box lid flew open, the contents of our “fridge” paint the interior. Yet mystifying, a the carton of eggs, unharmed.

I climb back into the cockpit. This is comparable to climbing a tree which is getting blown over, wearing your snow suit. I dig out the Edson “Pump on a board." With great difficulty, I pull everything out of the lazarette and am wishing this was more accessible. I remember clearly mounting this pump in a very strategic place back in Michigan. Wishing now we would have just glued it to the damn floor inside.

It’s awkward and heavy. I drop it through the companionway because I don’t have enough appendages to do it with grace and it smacks the galley floor and leaves a dent as predicted. One hose in the bilge, and the other out the companionway, Luke primes the pump. The hose begins to snake around as the weight of the water and misc. bilge debris sifts through. One pump at a time, we empty the flooded basement. It’s confirmed that we are not taking on any more water. Desiree remains in a relatively calm state lying a-hull.

L u k e : Sailing is resumed with less than third reef only. Holding steady course. No reaction from steering wheel, rudder missing or disconnected. Engine started and helped us with steerage. Using Hydrovane self steering rudder to bear us away onto course again. 20 nm from the lee of the headland. This decision was taken as the lee of the headland was near, and conditions were not worsening. Lying a-hull or heaving to for longer would have put us into nearby TSS *shipping lane* without the ability to track AIS movement after cockpit mounted screen was damaged by force of wave dislodging the mount and removal of mast head instruments to communicate over VHF. Engine stopped. Air in fuel lines.

Both sailors very wet. With wind chill 10 degree C, hypothermia likely. Having to hand steer from the transom with lots of spray. No dry clothing remaining down below, and 4 hours until sunrise, We again did 20 minute shifts with Hydrovane emergency tiller in between going down below to warm up. Wind remains consistent 35 to 40.

Luke musters up the courage to peel off his soaking layers, and replace them with what semi-dry gear is left in the closet on his 20 minutes off. I repeat after him and feel 1000x better. Changing out of wet clothes is a much more difficult task than one would think. I return to the stern to helm, it feels arctic, dramatic, and down right miserable. We are so close to the protection of the headland, I line myself up with the lighthouses ashore and steer. I tuck my face into my collar, and squint. The guiding lights become blurry neon lines. Luke shoves everything off the stove, and boils water. He delivers me hot chocolate and this greatly improves my moral. Game changer. I went from asking myself “what the fuck are you doing out here?” to “eh, this ain’t that bad” with a single sip.

Three hours later, that glow at the end of the earth we've been dying to see turns into an orange peel. The sun appears as if a kid cut it out of construction paper and stick glued it to the sky. I picture the kid who cut it out sitting just below the horizon, and pushing it up himself. It's bold. It's mesmerizing. I can feel its warmth already. It’s perfect. The seas are easing as we turn around the headland and the seagulls play games in the lee of our sails. The seagulls are having so much fun. I stare at them to distract me from my physical discomfort and they remind of the ability to make fun out of a shitty situation. The piece of orange construction paper forms a perfect circle and the surrounding sky becomes cozy. I breathe slowly and become numb to the spray of each wave.

We sailed to Lagos harbor entrance and dropped the anchor. Went about replacing fuel filters and bleeding air from the lines. Started cleaning up mess. Slept. The conclusion for potential knock down prevention is as follows - we could have done one of three things.

1) hove-to on port tack until day light, when boat started to struggle with following sea

2) drogue over the stern to slow the boat

3) never left the harbour…

I peel off my layers in the sunshine. The cockpit is so warm. The anchor secures us to planet earth and the breeze runs through the mop of hair on top of my head. We have a glass of wine at 10:00 am. We “cheers”, sitting there quietly. I tell Luke that I thought he was gone. My eyes swell with tears for a moment at the thought of being alone out there. We run through all the what-ifs. The should haves, would haves, could haves. One glass of wine goes down like water and I curl up in the cockpit into the smallest human I can become. Knees at my chest, head tucked in, I close my eyes under the sunshine and sleep.

A F T E R M A T H | N o v e m b e r 2 0 1 8

It didn’t take me more than 12 hours after the fact to be able to recognize this moment as one of the greatest of my life. I don't regret leaving the last port. We understand that we got lucky. That there are steps we could have taken to avoid this. That some of our decisions were right, and some of them were wrong. That it could have been much worse.

My retrospect quickly allowed me to see this as an exceptionally important lesson for Luke and me. Lukes sailed well over 25,000 miles, I’ve sailed over 12,000, but none of those previous miles matter until that one mile, one breaking wave. Never, have we ever, stopped learning, and that is sailings greatest gift.

The unpredictability of the sea, no matter the preparation, can be harrowing - but the thought of never leaving even more so. All we can do now, is move forward under the assumption we will eventually find ourselves in a similar situation, and take the appropriate preventative action.

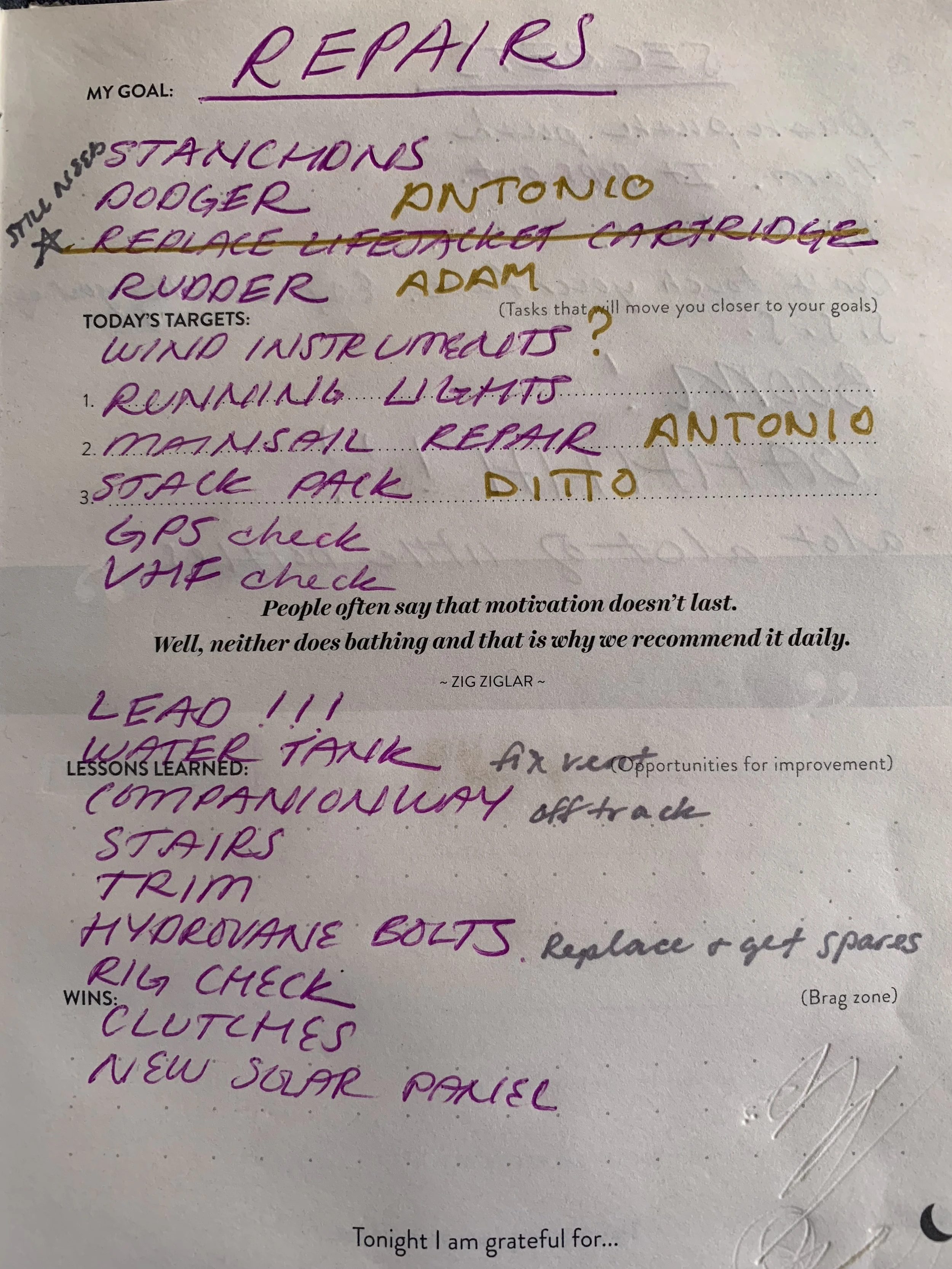

We put Desiree to rest on the hard here in Lagos, Portugal. Got married in Scotland and went back to Michigan for the summer. Now, 6 months later, we are back in Portugal dealing with the repercussions of a single wave - and prepping to sail across the Atlantic - again.

THANKS FOR VISITING OUR NEW SITE <3